Articles

Critical engagements with documentary photography

Extract:

The subheading to Camerawork 8, a special issue on the ‘Battle of Lewisham’, proclaims: ‘What are you taking pictures for?’. Why photograph? was a central concern of Half Moon Photography Workshop. In many ways the ‘why’ was easy to answer (although, as this issue showed, the reasons were many): what was more difficult was the issue of who - who could be a photographer, and what being a photographer meant.

In order to answer these questions, HMPW framed a radical reinvention of the medium and its practitioners, advancing a new concept of ‘community photography’. This was first outlined by Jo Spence in Camerawork 1 and elaborated on in Issue 13, which was dedicated to ‘Photography in the Community’. What Spence discusses in this first issue is a three-pronged attack on the mechanisms of mainstream image production and circulation in Britain.

The first weapon in this war was alternative or community presses, which offered photographers control over the fruits of their labour. Such publications could show solidarity and promote community action, providing an antidote to the individualism and sensationalism of traditional journalism.

The power was in having control over the means of image production: Spence recommends the use of photography as a tool by social activists. Through workshops and equipment loans, groups could encourage community feeling and help marginalised people represent themselves - gaining the skills to be critical of images and demand different depictions. Those who attended these workshops then became community documentarians, going out into the places in which they lived and worked to photograph the other residents and build a picture of a life from the inside contrary to popular stereotypes and ignorance.

Community photography, then, was about providing alternatives: alternative images, alternative photographers, and alternative channels of publication and distribution. Half Moon Photography Workshop attempted to provide for all three: in their gallery and magazine, their workshops, and promotion of photographers such as Derek Smith and George Plemper.

These ideas were radical in the Britain of the 1970s, where social documentary photography had fallen victim to its own success and become co-opted into mainstream imagery. However, in their suspicions and desire to create new photographers, HMPW were drawing on doubts already seeded within certain corners of the English documentary tradition.

Bill Brandt was a pioneer of British social documentary photography. His 1936 book ‘The English at Home’, a pictorial survey of British domesticity between rural and urban settings and across classes, appears a classic of the genre. However, this work was actually highly innovative, as Brandt responded to increasingly ambivalent feelings towards his claim to objectivity. Brandt mobilised a technique of juxtaposition drawn from the surrealists, in which commentary was produced in the collision of the photographs on facing pages. In this, Brandt directly intervened in the images, exposing the mechanics by which photographic meaning was produced, and foregrounding not only his creative role but his subjectivity.

Brandt’s suspicion of the photographer’s supposed ‘objectivity’ was also felt by the members of HMPW. They transformed this doubt into a new manifesto. It was not enough to recognise and acknowledge one’s limitations as a photographer: those biases still existed. Instead one needed to encourage more people to document themselves in order to counter the stereotypes of others.

In this community-based photography, HMPW found precedent in Mass Observation. Founded in 1937, and another surrealist-inspired endeavour, Mass Observation aimed to record everyday life in Britain through a network of volunteer observers who kept diaries, answered questionnaires, and took photographs of daily occurrences. Over 1,500 people were recruited from all social classes; ordinary people were given the necessary tools and encouraged to record their own lives and the lives of their communities.

In its desire for an ‘insider’s perspective’, Mass Observation chimed with HMPW’s ambitions, and the collective themselves were interested in this earlier project, dedicating an issue of Camerawork to the observers. Many of the photographers HMPW chose to exhibit also sat within this ethos: from Derek Smith’s photographs of his Teeside home, to George Plemper’s sensitive portraits of his pupils at Riverside. But HMPW differed from Mass Observation on two vital points.

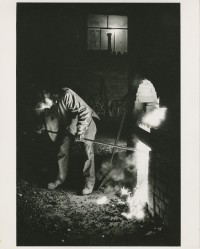

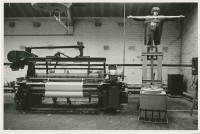

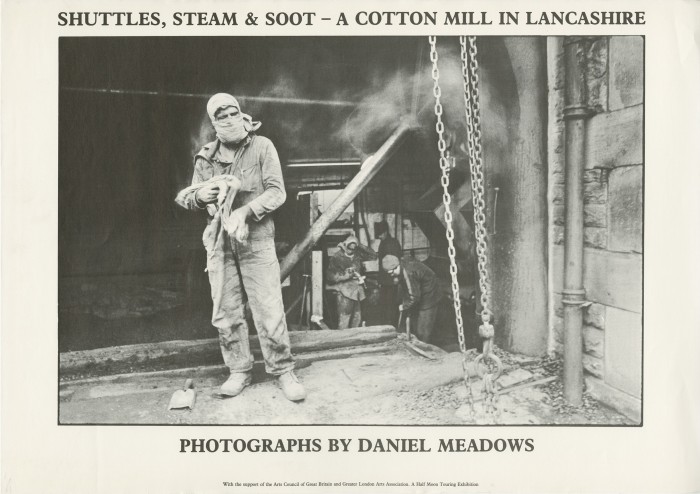

While Mass Observation had aimed at an objective record comprised of a great number of data points, many of HMPW’s photographers shared the tacit assumption of their subjectivity, even if the rhetoric of objective investigation was still present. Daniel Meadows’ Shuttles, Steam and Soot, was billed as a ‘serious investigation’ of the Lancashire cotton industry, but what actually enlivened the images for Meadows was the strangeness of the encounters - the interpersonal aspect.

Mass Observation had been instigated to create an archive of everyday life, but HMPW had far greater aspirations. As stated in their special issue: ‘to document alone is not enough - the process must be taken further and used to effect social change’. Change was always the purpose of HMPW’s projects, and social change relied upon a fundamental transformation of tradition. Suspicion of the photographer was transformed into a vision of community documentary, and community documentary was transformed into political action. Why take pictures was obvious, but HMPW’s chance of achieving that goal relied on a complex understanding of who (photographer and subject) gained by looking to the past as much as to the future.

Archive

668 results

The Non-conformists - Martin Parr

Lee Dam Swim. Johnny O' Hara (front) and Percy Bull (right) broke the ice to allow swim to take p...

Mike Goldwater Collection

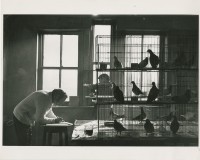

22nd March 1976; Opening for the 'Doing Photography' show with teenagers from Blackfriars Settlem...

Mike Goldwater Collection

22nd March 1976; Opening for the 'Doing Photography' show with teenagers from Blackfriars Settlem...

Mike Goldwater Collection

22nd March 1976; Opening for the 'Doing Photography' show with teenagers from Blackfriars Settlem...

Mike Goldwater Collection

22nd March 1976; Opening for the 'Doing Photography' show with teenagers from Blackfriars Settlem...

Mike Goldwater Collection

22nd March 1976; Opening for the 'Doing Photography' show with teenagers from Blackfriars Settlem...

Mike Goldwater Collection

February to March 1976; Claire Schwob's exhibition "Women, Who Are We?" Photo by Mike Goldwater

Mike Goldwater Collection

February to March 1976; Claire Schwob's exhibition "Women, Who Are We?" Photo by Mike Goldwater

Mike Goldwater Collection

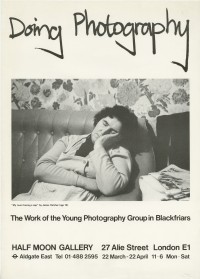

Doing Photography' show at the Blackfriars Settlement. Photo by Mike Goldwater

Mike Goldwater Collection

22nd March 1976; Opening for the 'Doing Photography' show with teenagers from Blackfriars Settlem...

Mike Goldwater Collection

June 1976; The opening for the Hackney Flashers show "Women .. Work in Hackney" at the Half Moon...

Mike Goldwater Collection

June 1976; The opening for the Hackney Flashers show "Women .. Work in Hackney" at the Half Moon...

People Portraits - Ed Barber

A series of postcards for the Half Moon Photography Workshop Touring Exhibition. Page...

People Portraits - Ed Barber

A series of postcards for the Half Moon Photography Workshop Touring Exhibition. Page 2 of 2

Men Photographed by Women - Maggie Ellenby, Pen...

Exhibition Poster for MEN photographed by women by Maggie Murray, Sally Greenhill, Angela Philips...