Articles

The politics of the Half Moon Photography Workshop

Extract:

In May 1975, Jo Spence and Terry Dennett formed Photography Workshop in Islington, ‘an independent educational, research, publishing and resource project’ designed to examine historical and contemporary uses of photography. Spence and Dennett were critical of contemporary photographic practices, particularly the professionalization of the sector and its growth within a competitive market. To them, these developments undermined alternative conceptions of the medium, with historical roots in the Labour movement of the 1930s.

The workshop grew out of our dissatisfaction with current trends in British photography and our desire to contribute, as photographers, to social change. – Photography Workshop, 1975

For them, the ‘amateur’, or non-professional photographer could act as an agent of democratic change. They saw a need to “demystify” photography, to break its association with an expert and exclusive form of knowledge, to resist its absorption in fine arts spheres, and to preserve it as a technology accessible to all.

Spence and Dennett were instrumental in uncovering the history of the British Workers’ Film and Photography movement of the 1930s. They believed that the oppositional photographic practices of the past should inspire contemporary practices on the Left, and saw photography as a radical tool for the expression and emancipation of minority voices. Their positions found an echo with members of Half Moon Gallery, who recognized common aims in the need to democratize photographic skills and give photography a role in activism. The two organizations decided to combine their energies and enthusiasm and the Half Moon Photography Workshop (HMPW) was formed in October 1975. The programme developed by the group was inspiring and ambitious. “We were embarking on a significantly bigger project than the gallery had been”. (Goldwater 2017)

The project sustaining HMPW was bold, based on common aims: to generate critical perspectives on documentary photography; to support politically-conscious photographic practices; to expand the ways that people could gain access to photography outside of established cultural institutions. HMPW played a central role in the politicization of debates on photographic documentary, both in the UK and beyond.

The project revolved around three main activities: gallery and touring exhibitions; publication of Camerawork magazine to provide forum for debate on critical photographic practices and the politics of representation; and the provision of an information and resource project. The latter focused on educational workshops, community darkrooms and practical advice on using photography within community politics. Spence and Dennett’s interest in alternative histories of photography and its uses in grassroots activism, as well as their experience in photography-based educational practices, gave coherence to that side of the project and informed the notion of community photography. Bethnal Green, with its socially and ethnically mixed population, proved an ideal context in which to use photography as a tool of empowerment. A ‘People’s Gallery’ would present photographs produced by local residents. ‘Establishing a photographic centre with workshop, darkrooms and gallery in a place like Bethnal Green at that time was a radical act in itself’, Ed Barber recalls.

HMPW’s approach, defined in its ‘Statement of Aims’ in issue 1 of Camerawork, had the overarching objective of placing photographic images and technology at the centre of processes of social change:

By exploring the application, scope and content of photography, we intend to demystify the process. We see this as part of the struggle to learn, to describe and to share experiences and so contribute to the process by which we grow in capacity and power to control our own lives.

This position was political in considering photography as a practice whose product (photographs) was ideological and which had political effects. To ‘demystify’ photography it was essential to change it from an exclusive form of knowledge and promote it as a democratic mode of expression accessible to all.

HMPW announced that “the running of HMPW [would] reflect our central concern in photography, which is not ‘Is it art?’ but ‘Who is it for?’ The organization was not concerned with modernist debates on the aesthetic merits of the medium. Rather, it sought to examine the plurality of photographic practices in light of their involvement in diverse social and cultural contexts.

HMPW appeared at a moment when similar intellectual debates happened around the ‘new art history’, which questioned the social and material contexts of artistic production, and in the emerging field of Cultural Studies, which was promoting critical theories of cultural practices, productions and institutions. Equally, HMPW shared an approach with History Workshop, whose first editorial, published in the History Workshop Journal (a couple of months after the first issue of Camerawork) stated its dedication to “making history a more democratic activity” and to encouraging the writing of socialist histories. The common reference to the workshop model indicated a preoccupation with collaborative modes of production and the sharing of skills and knowledge as methods of empowerment, be it through history writing or image-making.

Spence’s article ‘The Politics of Photography’, (Camerawork, Issue 1) gave coherence to HMPW’s agenda between 1975 and 1977. The article criticized standards and practices in the press, denouncing the sensationalist and de-politicizing tendencies in contemporary editorial photography. Spence called for photographic practices committed to challenging dominant representations and encouraged photographers to question the power relations inherent in the act of taking pictures. The article was the first to address the subject of community photography – a sign of Spence’s interest in the socially transformative potential of this form of photography. These alternative practices were first used by photographer Paul Carter from 1974 at the Blackfriars Settlement in London and replicated in different community projects across the country. These initiatives aimed to make photography accessible in local projects or campaigns, by teaching skills to local residents and opening darkrooms in community centres. The ambition was to make photography available to people as a tool to organize, agitate, or simply document local life in a bottom-up approach that was absent from mainstream photographic practices.

Organisational - Half Moon Photography Workshop...

Annual Report 1982-1983 - Incomplete: Front cover, contents and page 1 only

Organisational - Half Moon Photography Workshop...

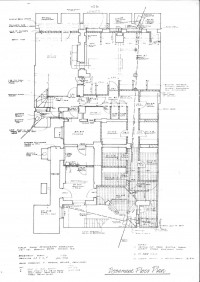

Darkroom Floor Plan - page 31, 32 and 32 of unknown document

Organisational - Half Moon Photography Workshop...

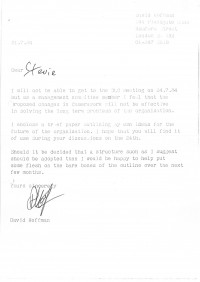

Proposal Paper and Covering Letter from David Hoffman 21 July

Organisational - Half Moon Photography Workshop...

Letter to Joanna Drew Director of Arts Council from Deborah Keys

Organisational - Half Moon Photography Workshop...

Covering letter to Advisory Committee Members from Noelle Goldman 6 May

Organisational - Half Moon Photography Workshop...

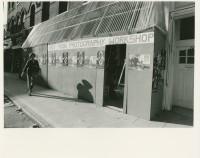

Photograph of the gallery during the preparation of the exhibition No Nuclear Weapons by Peter Ke...