Behind the Lens: George Plemper

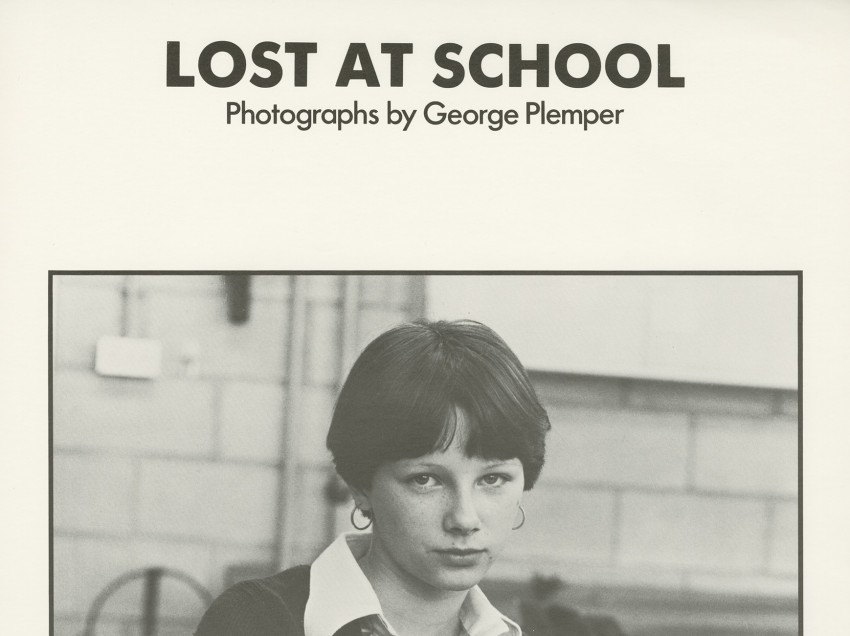

When George Plemper was a teacher at Thamesmead School in South London, he began photographing his students. These children had been written off by many as ‘problem kids’, but through photography, George found a way to instil them with confidence and help others see them in the same positive light he did.

After leaving teaching, George took these images to Ed Barber and Mike Goldwater, and they became the basis for the Half Moon Photography Touring Show ‘Lost at School’. Forty years later, George talks to us about this project.

The title ‘Lost at School’ is very evocative. Where did that title come from, and what was your reaction to it then and now?

The simplest answer is that I would often stand in front of a class and experience a type of out of body experience where I would look at myself and think “how on Earth did you get here!” Holding a camera brought me back to myself.

When I am asked about my time as a school teacher I often describe myself as being very idealistic, and often equate my idealism to naivety. It is only recently that I have come to understand that my idealism reflected a personal view of reality that I see in the ineffable, transcendent quality of some of the great photographers of the 19thand early 20th centuries. I feel the love and respect that Lewis Hine had for the children and the struggling working class. Looking at his photographs I entered his world and gained a sense of his reality, his consciousness.

Trying to select the images for the exhibition, I was desperate to put together a collection that would give people a sense of my world. To me, documentary photography is an art, but for many documentary photographers at the time that idea was appalling. The talk at the time was that the camera was a liar and this led to the belief that all photographs needed to be placed in a narrative context and explained by detailed captions. Seen from this narrow perspective, the role of photography was to denounce, to explain, to show. I found this approach to be deeply unsatisfactory. I looked for a title that went beyond the descriptive: that hinted at a dimension in portraiture which went beyond a superficial, surface description of the person(s) in front of the camera.

I gave little thought to the title after that and prepared the exhibition which was first shown at The UCL Institute of Education. I got the first hint that the title could be misinterpreted when I was approached by a lady at the opening of the show. She told me she liked the work but did not understand why I was saying that the children were lost at school, they certainly did not look like it! I laughed and told her that the title was not about the children, it was about me and my struggles as a teacher. When I approached the Thamesmead Neighbourhood Offices to ask them to put up the posters in their facilities they refused. Now I understand that they were quite right to do so. Naively, I never expected anyone to react this way. Surely they could see that I was suggesting that it was the school system that was failing our young people.

The photographs at Thamesmead School, although they were taken over 40 years ago now, still provoke deep reactions in viewers. It is possible to feel your connection to the children even across all these years. What do you make of the continued appeal of these pictures, and how do you feel looking back on them at this distance?

The short and unsatisfactory answer is that I do not know. Diane Arbus once said that her photographs never came out the way that she expected. The cynics among us would say that this is simply false modesty, but I think it’s a very profound and important statement that hints at a metaphysical aspect to photography. Few are willing to recognise this. I cannot explain the continued appeal of my photographs without referring to this quality.

A few years after I took these pictures, I put them to one side in order to make a living and it was only after thirty years that I took them out to look at them again. It was a wonderful and surprising experience. Until then I would tell myself that nothing good came from my time as a teacher – they were my “wilderness years” so to speak – yet the photographs showed me in no uncertain terms that there was a lot of kindness and good things happening then. I felt embarrassed that I took so much for granted back then.

It seems that children now live in such an image-saturated society and are constantly creating images of themselves, however the magic of these images is in their unexpected quality and the relationship between subject and photographer which is absent in teenage selfie-culture. Did the children express any particular reaction to being photographed, or to seeing these images of themselves?

At first the children were suspicious: it was unusual for a teacher to take so many photographs, and you can see their scepticism in the early photographs. To overcome their suspicions, I tried to turn the photographic process into a game or a distraction from the rigours/stresses of the classroom. I would always give the children copies of the photographs that I took and they would take them home. They could see in the photographs that I liked them and everyone likes to be liked. Not everyone wanted the attention and so I would leave them alone.

Recently I have been involved with Lucia Tambini who was making a film following the lives of a group of women who I photographed at Riverside School. One women showed Lucia one of the photographs I gave her 40 years ago. She did not have a good time at Riverside, but in spite of this she kept the photograph. It was all battered and torn and was obviously important to her. I still have the image of the battered photograph in my mind.

Interview by Frances Whorrall-Campbell

Posted by Carla Mitchell on 5th November 2019 at 12:00am