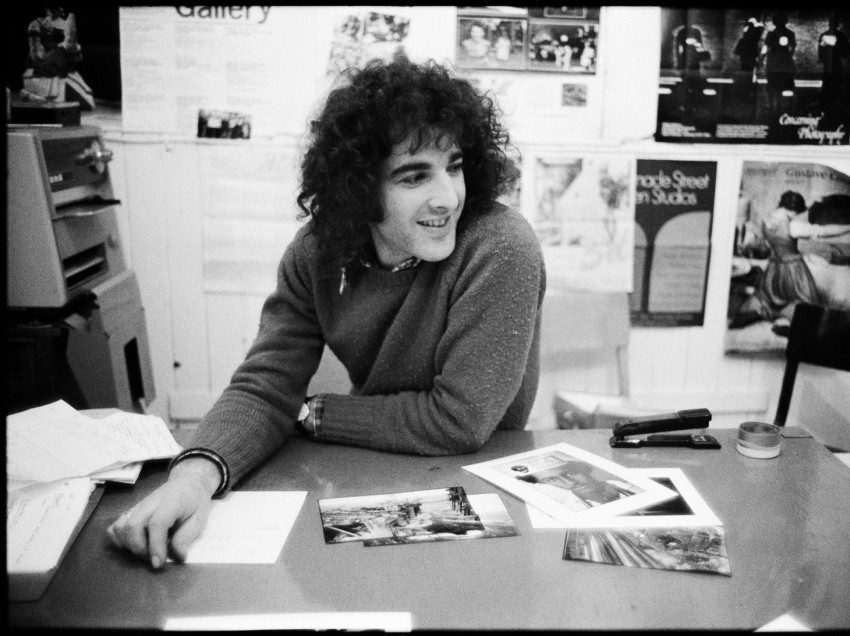

Behind the Lens: Mike Goldwater

Behind the Lens 02. Mike Goldwater

Mike Goldwater was the director of the Half Moon Gallery when Camerawork Magazine was founded. He speaks to us about his role in establishing this publication and explains the magazine’s radical aesthetic.

How did Camerawork magazine emerge out of the work that was being done at the Half Moon Gallery? Do you feel it was an extension of the gallery’s remit, or an attempt to answer more questions or solve problems the gallery format couldn’t?

In retrospect you could say that Camerawork magazine emerged as a natural evolution of the energy and questioning attitudes of the people the gallery had attracted. We somehow tapped into the zeitgeist of the time. The magazine allowed us to reach a wider audience, explore ideas and create a dialogue that was not possible with the gallery format alone. Specifically, the magazine emerged organically from a seminar series held at the gallery.

The actual events were that, in the autumn of 1974, after I had my exhibition ‘Estate’ at the Half Moon Gallery, Paul Trevor (who with Julia Meadows had been running the gallery) asked me to take over. He was going to Liverpool to begin his Exit Project with two other photographers. I wasn’t keen to take on the role at first. I was 23, just beginning my career as a photographer, but Paul suggested we organise a series of seminars on photography to put the gallery on the map and I found this idea intriguing.

The photographer George Solomonides was also interested, and the three of us put together what became a series of six seminars, held monthly under the title “Camera Obscured?” As the series poster said: the aim was to “assess the current state of British photography by examining the way that photography is used in our society and highlighting the conflicts of interest that arise”.

The seminars were a great success. One of the people who came to every seminar was Tom Picton, lecturer in Photography at the Royal College of Art and freelance photographer for Time-Life. As an audience member, he asked some of the most perceptive questions. We invited him to chair the last seminar and he was keen to be involved in whatever we did next.

Meanwhile, Jo Spence and Terry Dennett, who first met at one of the seminars, had put together a proposal for their Photography Workshop. Paul, George and I liked their ideas, which chimed in many ways with ours. We had a series of meetings with Jo and Terry, which Tom also attended, and decided to join forces to form the Half Moon Photography Workshop.

George wanted to return to his photographic career (while still doing our accounts), so Jo joined me on the staff. The Half Moon theatre offered us a small office at the rear of the building, a glass roofed lean-to on the first floor that had been a pigeon loft, but we cleaned it up and began work.

We – Paul, myself, Jo, Terry, Tom Picton, George, and others in an informal collective – set ourselves an ambitious programme. We planned to start a publishing project, run education workshops and an information and advice service while continuing our monthly exhibitions.

We formed an editorial group and began putting ideas together for the first issue of our magazine. Jo, Tom, Terry and Paul began writing articles for the first issue. Jo was interested primarily in the politics of photography and the use of photography in the community context. Tom’s way into examining social and political issues was through journalism and he often employed a keen wit in his interviews and articles. Terry, who was staff photographer at the London Zoo, was keen on alternative technology. His Camerawork features would focus primarily on interesting low budget alternatives and demystifying the chemical processes.

How was the innovative tabloid > a4 format arrived at? Camerawork was clearly very concerned with the context in which images were viewed and circulated, and was this specific aesthetic an attempt to answer these questions?

Tom came to a meeting with a copy of the American photo magazine Afterimage, and suggested we adopt their format. Afterimage folded out from an A4 format to A3 and opened to A2, allowing for large images. None of us had seen this radical format before – unstapled, portable but expansive, allowing images to be viewed at up to gallery size. We loved the idea. Expression Printers in Dalston had been printing our high quality A3 exhibition posters and I was keen for any publication we produced to be of the same standard. Expression confirmed that they could print this format and to keep costs down, we planned to fold the magazine ourselves from the printed A2 sheets down to A4.

In 1976 there was nothing on the English market remotely like Camerawork. The British Journal of Photography was largely a technical magazine, Amateur Photographer was aimed at the camera clubs and led by advertising and Creative Camera was an art magazine with little text. We felt empowered and set out to be radical.

"Camerawork is designed to provide a forum for the exchange of ideas, views and information on photography and other forms of communication. By exploring the application, scope and content of photography, we intend to demystify the process. We see this as part of the struggle to learn, to describe experiences and so contribute to the process by which we grow in capacity and power to control our own lives."

Camerawork Magazine masthead.

The Arts Council, in response to the funding application that Jo and I put together for the HMPW, said they would match funds we could raise ourselves. So in parallel with getting the magazine ready for launch in February 1976 we also organised our first photographic jumble sale and print auction, held in the Half Moon Theatre on 22nd Feb 1976. We raised £800, more than £5,000 in today’s money. Volunteers played a vital part in this project.

Two people who volunteered at that time were Marilyn Noad and Janet Goldberg. Marilyn could touch-type, and produced all the magazine galleys on an IBM electric ‘golf-ball’ (then new technology) typewriter that I managed to get access to for free after hours. Marilyn and I would often work through the night to get it all done. Janet, a student at Syracuse University, had experience of paste-up and laid out much of the magazine. We aimed to keep the look clean and simple, and the design evolved as we gained experience. Tom’s journalistic and publishing experience were invaluable here too.

Legend has it that the first issue of Camerawork was produced in an all-night session at the gallery’s Chalk Farm studios. What was the atmosphere like in these ‘folding parties’? Did the content and discussions of these sessions alter the magazine itself, or feed into future issues?

The evening before we were due to take the first issue’s final page layouts to Expression Printers, we had still not decided on the magazine’s name. We were packed into our little office at the back of the Half Moon theatre, finishing off the paste-up and bouncing around ideas. After much discussion, and voting, Camerawork emerged as the frontrunner.

Jo was at home, ill with flu. Paul called her and we all cheered when she agreed with the name Camerawork. The only sheet of Letraset we had left that had all the letters in the right font size was Stencil Bold, so that became our logo.

By Autumn 1975, Camden Council had closed The Dairy in Chalk Farm where my darkroom had been; the old dairy was being razed down to clear land for redevelopment. Space Studios offered me a larger studio in the stable block of an old piano factory in Fitzroy Road, Primrose Hill. I built a new darkroom there and still had room for a good studio area. This is where we held Sunday folding sessions for the first seven issues of Camerawork.

We could usually gather 10 to 15 volunteers. Folding several thousand copies of Camerawork would take all day, we’d provide lunch and in the evening we’d have a party. I think everyone enjoyed the discussions as we worked and the sense of collective endeavour. People were glad to be involved and some volunteers wrote articles for the magazine or had letters published on Camerawork’s Lively Letters page.

Interviewed by Frances Whorrall-Campbell.

See more of Mike Goldwaters' work here .

Posted by Ruby Rees-Sheridan on 10th July 2019 at 12:00am