Behind the Lens: Nick Hedges

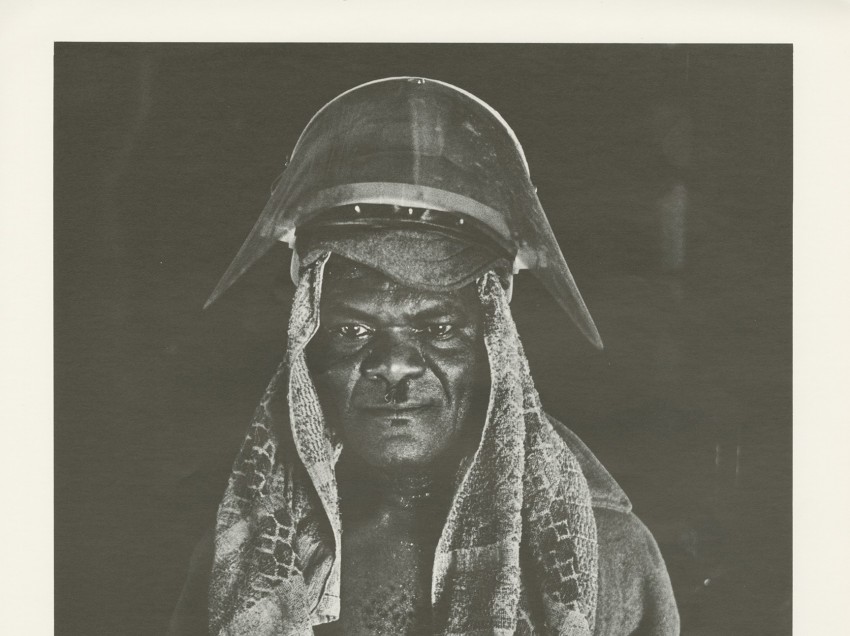

Nick Hedges’ exhibition ‘Factory Photographs’ was shown at the Half Moon Theatre in 1978. The exhibition was a documentary study in text and images of factories in the Midlands. We spoke to Nick about the project and how it shaped his views on photography.

You interviewed many workers at the factories where you photographed. Why did you think that it was important as a photographer to speak to people, and did it change the way you approached the workers as subjects, or how they related to you as a photographer?

It has always been my approach to documentary photography to talk to everyone I photograph. In the first case to explain why I want to take photographs, secondly because I want to know more about the work, the living conditions, the culture and the personality of the person I’m photographing. In doing this it is possible to establish a more informed and intimate relationship with your subject. This fundamentally changes the nature of the photograph. In the project I worked on about factories and steel works I took this a stage further. Having completed my photographic work I returned with an audio cassette tape recorder and taped interviews and conversations with people I’d photographed. This was intended to add their voices to the project so that the photographs became more inclusive. I transcribed the interviews, and with Huw Beynon we were able to include workers’ voices in the book ‘Born to Work’.

Camerawork promoted a critical view not only of images but the structures that surrounded their making and reception, often questioning the ‘objectivity’ of documentary photography. How did you reconcile the desire to gather and record information objectively and accurately with the subjective position of the photographer?

The question of ‘objectivity’ and ‘subjectivity’ seems to have bedevilled photography since its inception. What Camerawork did so well was to enlighten its audience to the unseen factors that govern the production of photographs, their publication and distribution, and the consumption of images. What has driven me all the time I have been a photographer is my need to have a clear understanding of why and who I am photographing.

Working for Shelter was governed by several factors. I chose to work there because I recognised that a significant number of families in Britain were living in appalling housing conditions; this fact was largely unknown by the majority of the population, and it was a low priority of the government. The charity had to make the situation better known, and more recognised by central government and local authorities. Taking unposed documentary photographs and using them with interviews with the families became our way of publicising the situation.

At the same time, because a charity has to raise money to enable it to fund housing associations, the edit of the photographs tended to overuse both pictures of children and mothers and children. They were ‘innocent victims’. Blame could not be attached. In purist terms objectivity was compromised by the message being shaped by its use and its intended audience. This was a compromise that I was prepared to work with. That record is in no way a false account of the housing situation in the late 60s and early 70s, but it was made for a purpose. All photographs are made for a purpose. To suggest otherwise is an illusion. The purpose is sometimes disguised, it is our job to reveal it and explain it. My project on photographing factory work enabled me to work purely for myself, in that I chose the subject, I controlled the method, the execution and the subsequent publication and exhibition. But it would be foolish and dishonest to suggest that it was totally objective: nothing ever can be.

This project produced very different images of the ‘worker’ than were present in mainstream media at the time. The workers emerge as individual characters who have a relationship to their colleagues, rather than as alienated parts in a machine. How important was that sense of challenging mainstream media to your project, or was it a product of getting to know the workers during your time with them?

It was important to challenge the image of factory work projected by mainstream media. There were two views of work that appeared in newspapers, magazines and on television in the 1970s. These were either about disputes and strikes, a view that suggested that conflict was the normal state of working life, or there were features about new products, and the wonders of new technology. What was entirely missing was what people actually did, what sustained them in seemingly endless tedious working situations, or in environments that were both hazardous and physically exhausting. Through the project I began to understand the immense importance of relationships at work, the real significance of friendships, mutual respect and interdependence. The skills, craft and artistry demonstrated every minute of every day, and the sensation of self worth that this fostered. When I began the project in 1976 I had no idea that within ten years the destructive economics of Thatcher’s government would lay waste a century of industrial working culture, and break the spirit and soul of this country’s working communities.

I was led towards the project by Studs Terkel’s monumental book ‘Working’. It was through talking and observing and photographing men and women workers that I gained a profound respect for their lives, and for the contribution that they made and continue to make to our wellbeing and to the liberties that this country enjoys.

Interview by Frances Whorrall-Campbell

Posted by Ruby Rees-Sheridan on 4th October 2019 at 12:00am