Behind the Lens: Tricia Widdison

In the early 1970s Tricia Widdison moved with her husband David to Toxteth, Liverpool, an area then wracked with economic stagnation and unemployment. Together they set about documenting their community. Tricia and David sought to represent the people of Toxteth from their own perspective, as an antidote to the romanticisation or castigation with which they were so often depicted.

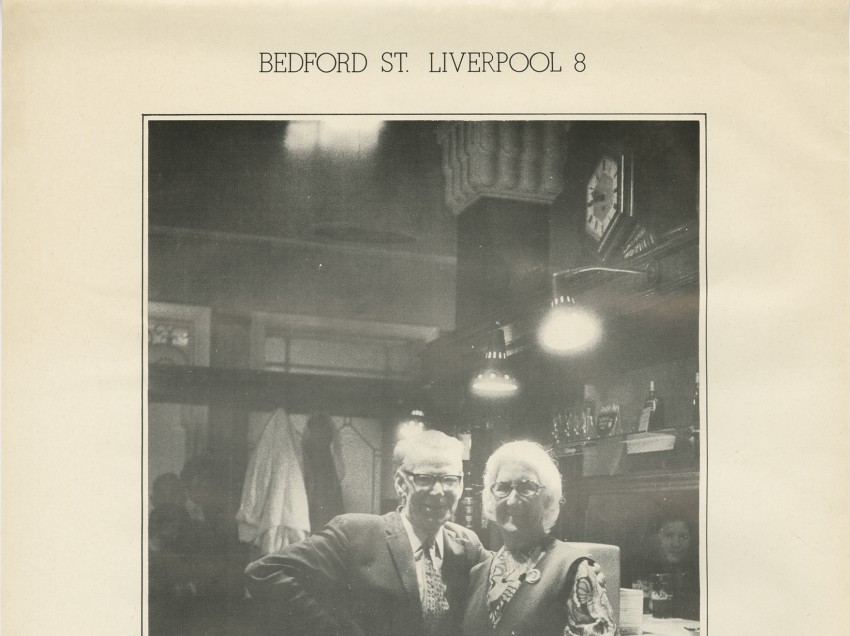

Tricia's photographs formed the exhibition ‘Bedford St. Liverpool 8’, which opened at Half Moon Gallery in May 1973. We spoke to her about the project.

You came to Liverpool in the early 1970s and set about photographing the streets around where you lived in Toxteth which were threatened with demolition. How did you feel as an outsider coming in to document everyday life in the community against the backdrop of this struggle? How important was it for you to feel embraced by the local people?

I was always fascinated by photographs. A photographer friend in London suggested that I bought a camera, which I duly did and set about to explore the medium of photography.

I met [my husband] David at an arts venue in London. He was a Merseysider and at the time was studying at the university there. He was living in Liverpool 8, a district wracked by war damage, planning blight and poverty. Much had been written about the area but he realised that not much has been said about the people who lived there. He wanted to write about the community in which he lived, so I moved into the area and we worked together as a writer and photographer.

David knew people in the area, and it was suggested that we start by talking with one of the shopkeepers. From there he suggested other people we should talk with and so we built up an intriguing network of contacts. We were very much accepted and I didn’t feel like I was an intruder, especially since David was from Liverpool and lived amongst them.

What did you feel your role was as a photographer there? Did you feel as though you were challenging negative media stereotypes about the region and residents, or perhaps you felt that your project was an outlet for the local people to voice their upset about the destruction of their community?

This question I think can be answered by an extract from an article David wrote for the Merseyside Arts Alive Magazine in March 1973 describing the exhibition we had at the Liverpool Academy Gallery in 1972:

Liverpool 8 had more social workers than any other district in Britain, and had had its ample share of surveys and reports. As the poetry of the Liverpool poets began to creep discreetly into the more respectable academic environments, the social side of Liverpool 8 had become a case-book, a textbook example.

From both sides, the writers and photographers came in and pounced on the area’s architecture, its poverty, its romance, its Adrian Henri; the result is about as much documentation as any equivalent area has ever had. Made into a single pile, it would top the St John’s tower, etc., etc. There seemed little prospect of saying anything new: it had all been done before. Or had it?

We [Tricia and David] examined what had been written and found that there in fact was a great deal still to be said. We found, for instance, that there were certain views and prospects which appeared in most of the Liverpool books, and certain standard shots that cropped up time and time again - the cobbles in a back alley, iron lamp standards, an old woman looking out of a window - and certain topics were constantly written about. The area had become a source-book of symbols; the photographs were symbols of poverty, not pictures of poor people; the bombed houses were symbols of decay, not houses and homes. On the other hand, the sociologists produced tables of statistics in which people were reduced to age-categories and “numbers of children in family”; the reports were made up from circulated questionnaires, and somewhere in all the facts and figures the people had somehow got lost again.

And so we decided to approach the area from the starting point of the community and the people who made it up. In the several months we spent photographing and talking to residents, the two streets we were looking at changed their character dramatically; Falkner Street had been largely bought by the university, and Bedford Street was being built up by the Corporation. As a result, the community dispersed, and people moved in and others rehoused. The pictures and the text had a sadly historical aspect about them even then. There were few areas of the city centre which could claim as strong a community spirit as this one had.

Your husband David wrote texts intended to accompany your photographs, describing the social history of the area and its residents. Could you speak about this collaboration, and how you see the role of texts in relation to documentary photography and this project?

I consider David’s text is an integral part of the story. The text in no way sets out to describe the photographs, the photographs speak for themselves - the text brings another dimension to the visual story and someone else’s point of view.

Interview by Frances Whorrall-Campbell

Posted by Ruby Rees-Sheridan on 3rd September 2019 at 12:00am