Articles

A brief history of the publication

Extract:

Camerawork as a magazine had a quality about it - when I first saw a copy in 1976 I'd never seen a publication like it and I still haven't. It stopped me in my tracks. The A2>A4 folding format, the print quality - amazing for single pass litho - the picture spreads and the articles, they all set it apart from any other photo-magazines of that period – Ed Barber

Camerawork is designed to provide a forum for the exchange of ideas, views and information on photography and other forms of communication. By exploring the application, scope and content of photography, we intend to demystify the process. We see this as part of the struggle to learn, to describe and to share experiences and so contribute to the process by which we grow in capacity and power to control our own lives. – Camerawork magazine masthead, issues 1-19

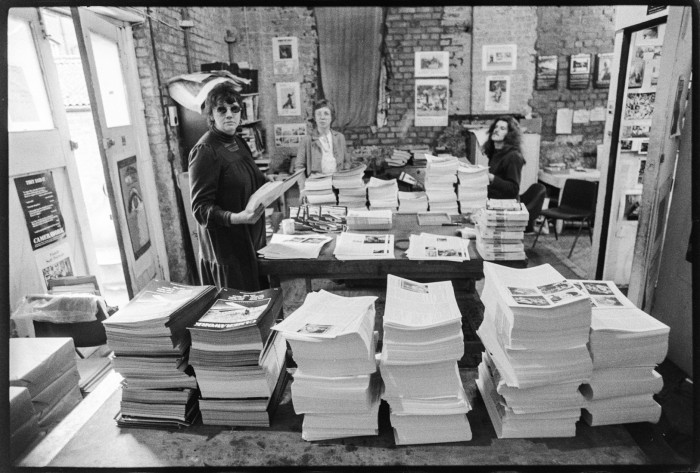

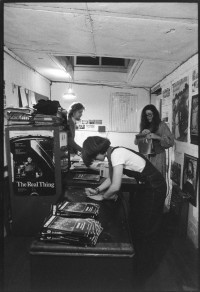

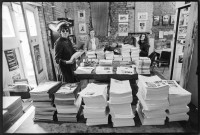

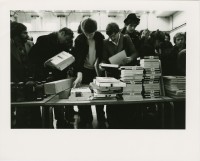

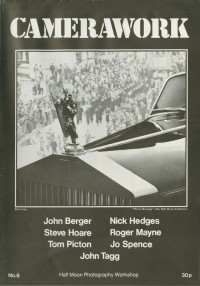

A key part of Half Moon Photography Workshop’s programme was the publication of a magazine. Camerawork was first published in February 1976, using a broadsheet format – sheets of A2 paper folded to A3, then to A4. Stencil bold, the only large typeface that they had, was used for the title. Expression Printers’ stark black and white printing was highly effective. Tony Bock, Terry Dennett, Roger Eaton, Mike Goldwater, Janet Goldberg, Marilyn Noad, Tom Picton, Jo Spence, George Solomonides and Paul Trevor produced the first issue of Camerawork, put together at a marathon all-night session in Goldwater’s studio in Chalk Farm, fuelled by coffee and beigels. After the first issue they drew Ed Barber, who was recruited to work on the accounts but quickly joined the magazine collective, along with Shirley Read, Liz Heron, Richard Platt and Jenny Matthews and many others.

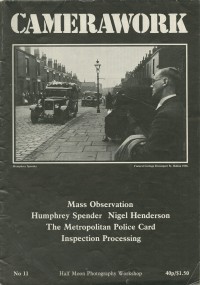

The early magazine had a pluralist, open and improvisational approach, encompassing articles on renowned photographers including Bill Brandt, Paul Strand and Brassai alongside alternative histories of photography, grassroots practice and DIY pages on photographic processes. Regular critiques by leading writers such as John Berger, Victor Burgin and John Tagg explored the ideological constructions shaping photographic practice. Camerawork rapidly established itself as a forum for critical debates on the politics of documentary representation, the role of the photographer and the use of the medium in oppositional politics. As the use of larger images increased, a centre spread was added that could be pulled out as a poster. The first was Robert Golden’s photograph of miners waiting for their shift at Kellingley Colliery, Yorkshire. The second, Richard Greenhill’s dramatic image of his wife Sally minutes after giving birth to their daughter.

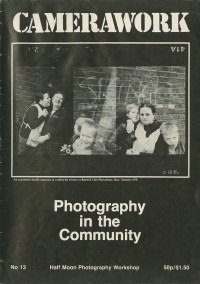

Camerawork included visually compelling, thematic issues such as Lewisham, the Picture Story, Portraits, Photography in the Community and Reporting on Northern Ireland. The magazine became a key platform for photography addressing left-wing oppositional politics. Reports of anti-racist demonstrations highlighted community action whilst shedding light on police brutality. Issue 14 on Northern Ireland proved highly contentious at a time of significant press censorship. Coverage of anti-nuclear protests helped to galvanise support for the revival of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

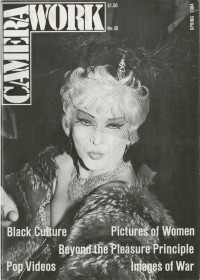

The magazine’s emphasis changed in the later issues, focusing more on broader politics of representation rather than solely photographic practice. Content expanded to include film, video, tape/slide and television with an increased emphasis on analysing mainstream media.

Alongside this Camerawork’s focus became explicitly political from issue 20 (1980) in response to the election of Margaret Thatcher. The magazine’s a new masthead stated that it was ‘a journal of the politics of photography’. The editorial read: ‘We must pursue this politics of the image into all the struggles that affect our lives: struggles over class, patriarchy, power knowledge, communication and education’. This went too far for the Arts Council, who reminded Camerawork that its subsidy was ‘on the basis of its attention to photography and not as a platform for political comment’. By issue 25 the masthead had changed to the neutral statement that: ‘Camerawork aims to promote debate and discussion on politics, photography and representation’.

Thatcherism marked a crisis for left cultural approaches. Black and white photography no longer felt like a connection to a radical past. ‘The Fight to Work’, a four-page spread in Camerawork 18, showed vivid images of the steel workers strike, and called for photography that was neither mass media representation of intimidating pickets, nor abstracted images of heroic workers. It was one of the last articles of its kind. In ‘Loves Labour Lost’, Camerawork 29, Kathy Myers argued that Labour’s posters helped lose them the 1983 election with their use of outdated images of working-class men in flat caps. Visual artists should ‘combine the visual sophistication of advertising with the social insight needed to provide new visions and fantasies for the future’. In her interview with Stuart Hall he also called for a new kind of imagery: ‘The left has to look around and see the language that consumer capitalism speaks to people in’. These arguments reflected the left’s seeming inability to combat a Thatcherite world in which there was ‘no such thing as society’.

Increasingly the concerns of many artists and photographers moved away from social struggle towards a focus on post-modern theories of representation and popular culture. The last four issues of Camerawork are noticeably different. The design of issue 29 is reminiscent of City Limits, with articles on video exhibition, graphic design of album covers and cable music television by Malcolm McLaren. Later issues of Camerawork changed direction several times. From issue 29 the format was altered to an A4 magazine style, with, for the first time, an editor: first Kathy Myers, then Liz Wells. But production faltered with lack of funding, and a loss of organisational direction. The magazine folded after issue 32 in 1985.

During its ten years, Camerawork made a profound impact on debates about the politics of photography and representation, and brought an extraordinary range and breadth of documentary and photojournalistic work to audiences worldwide. The role and influence of the magazine has often been historically overlooked within the canon of established British photographic history. The aim of this digital resource is to open up the understanding and appreciation of this renowned publication for a new generation.

Archive

17 results

Oral History Excerpt - Jill Pack

Pack discusses Mass Observation, which served as an ‘anthropology of Britain’.

Oral History Excerpt - Don Slater

Slater discusses Half Moon/Camerawork’s internal debates regarding representing politics and his ...

Oral History Excerpt - Don Slater

Collective working and democratic decision-making informed almost all parts of the creative proce...

Oral History Excerpt - Don Slater

Slater reflects on his “community photography” article for Camerawork and the magazine’s goal of ...

Oral History Excerpt - Don Slater

Slater discusses the new era of photography Camerawork was a part of: it did not have to be exclu...

Oral History Excerpt - Don Slater

Slater discusses his current work and teachings with an eye towards how it relates to his time at...

Oral History Excerpt - Jill Pack

Pack goes into detail on Camerawork Magazine's extraordinary format and printing process.

Oral History Excerpt - Jill Pack

Pack reflects on an initiative with group of women who were published in Camerawork and later rep...

Oral History Excerpt - Paul Trevor

Trevor discussing the original intent of Camerawork’s first issue, which focused on documentary p...

Oral History Excerpt - Paul Trevor

The inspiration for the ‘Mass Observation’ issue of Camerawork came out of a Royal College of Art...

Oral History Excerpt - Paul Trevor

Trevor discussing many of the contemporaries that worked in or with Camerawork Magazine through t...

Oral History Excerpt - Paul Trevor

Trevor discussing the spirit of the magazine and its roots in the community, and representing the...

Oral History Excerpt - Paul Trevor

Trevor discussing Camerawork Magazine’s promotion of British documentary photography.

Oral History Excerpt - Paul Trevor

Trevor discussing the 70s zeitgeist and political climate that allowed for Camerawork to thrive.

Oral History Excerpt - Paul Trevor

Trevor discussing Half Moon’s usage of flyposting, particularly in advertising exhibitions and fo...

Oral History Excerpt - Paul Trevor

Trevor discussing his photojournalistic documentation of the Bengali protests against institution...